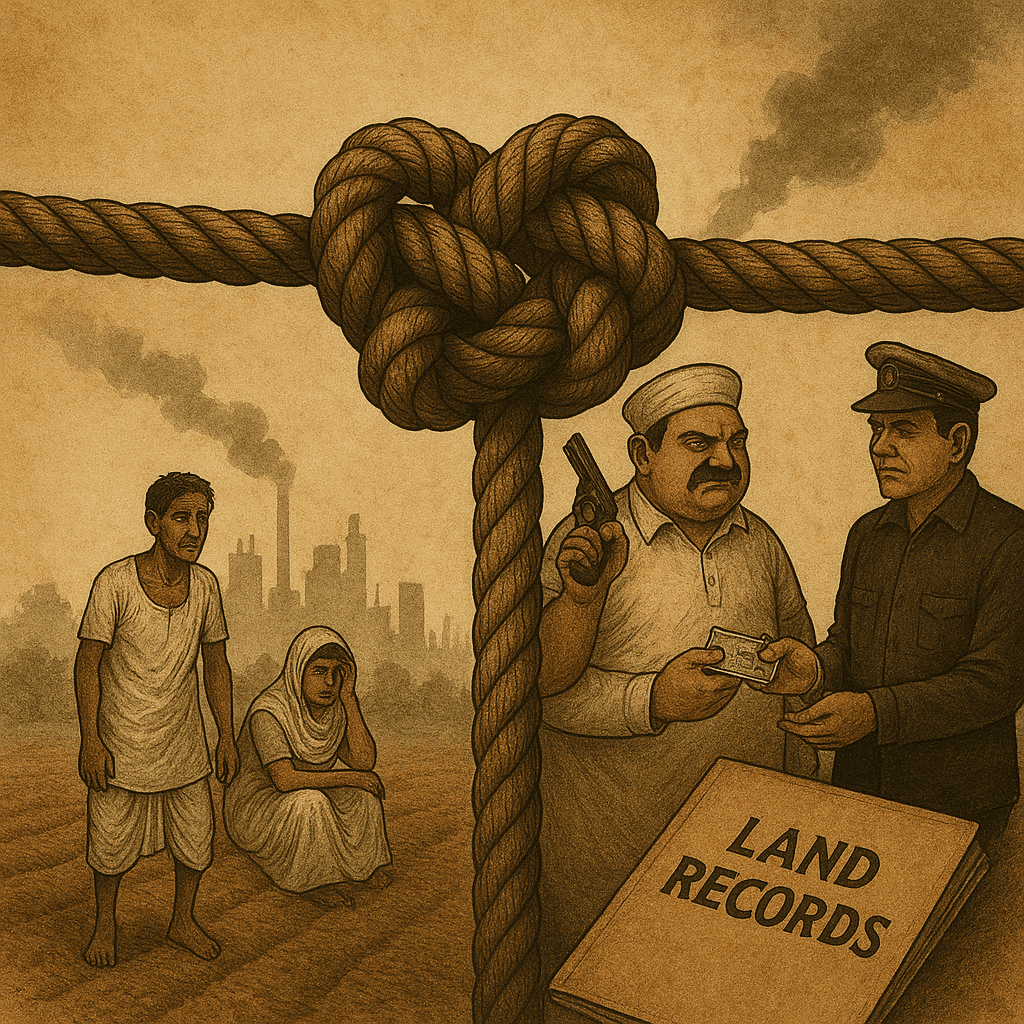

Land in India is not just territory – it embodies identity, power and livelihood for millions. Yet decades of failed reform have left a fragmented and opaque land system. Complex deed chains instead of state-guaranteed titles force buyers to hunt through antiquated records prsindia.org. In practice only about 9% of villages have completed modern survey work and just 26% of cadastral maps are linked to ownership rolls prsindia.org. The result is a toxic web: land disputes clog two-thirds of all pending civil cases, dragging on for two decades or more prsindia.org. Meanwhile a shadow economy of crime and corruption thrives. Without urgent reform – digitizing records, guaranteeing titles and crushing the land-mafia – India’s agriculture, industry and cities will remain trapped under the weight of this “land knot.”

The Legacy of Inequity

India’s colonial inheritance set the stage. Under the zamindari and related systems a tiny elite held sway over most land. At independence, roughly 7% of landowners controlled 54% of the land effectivelaws.com, whereas 28% of smallholders shared only 6% effectivelaws.com. Post-Independence reforms abolished big landlords and gave tenancy rights – freeing millions (around 30 lakh tenants gained title to their land effectivelaws.com). But weak enforcement and loopholes blunted these gains. Many elites evaded land ceilings through benami transfers or by quietly retaining control. Even today land distribution remains heavily skewed, with marginal farmers insecure in tenure. This deep inequality is the seedbed of social unrest and inefficiency. Workers denied asset ownership lack investment incentives, and dispossessed groups (including tribal communities) are prone to conflict when basic land rights are ignored effectivelaws.comvajiramandravi.com.

Unclear Titles and Institutional Chaos

Today India’s land ownership regime is presumptive, not conclusive. A property deed by itself is not a state-backed title but merely evidence of transfer; the onus is on the buyer to verify past ownership prsindia.org. Discrepancies are common because records live in silos – with revenue, registration and cadastral agencies all running separate systems prsindia.org. In practice, hardly any area has been recently surveyed: only about 9% of villages have completed modern re-surveys, and barely 26% of maps are linked to the official Records of Rights prsindia.org. This fragmentation and obsolescence breed confusion over boundaries.

The consequences are staggering. Land cases dominate India’s courts – roughly two-thirds of all pending civil suits are land disputes prsindia.org – locking up trillions of rupees in limbo. Cases routinely languish for twenty years or more prsindia.org. Investors steer clear of such paralysis: industrial and infrastructure projects routinely stall on the brink of acquisition. In short, unclear titles immobilize assets, deter investment and sap economic vitality.

From Bhumafia to Land-Grab Gangs

In the vacuum left by institutional failure, criminal networks have seized control of land conflicts. “Bhumafia” – the land mafia – churn out forged documents and terror tactics to steal land. In one recent case, a notorious UP gang was found to have fraudulently executed 250 fake sale deeds covering ₹100 crore of real estate timesofindia.indiatimes.com. These impostors ignored zoning laws: they sold plots without changing land use or approvals. They deliberately under-valued deals to evade stamp duties, hiding a large “cash” component that was laundered timesofindia.indiatimes.com. The Enforcement Directorate’s intervention in such scams has recovered crores of rupees in assets, illustrating how illicit money is funneled into land timesofindia.indiatimes.com.

Criminal tactics often prey on the vulnerable. Some gangs obtain fake death certificates or identity documents to register land in their names. For example, in Aurangabad police uncovered a scheme where impostors forged an elderly man’s death certificate to seize his five-acre farm timesofindia.indiatimes.comtimesofindia.indiatimes.com. They submitted the counterfeit papers to courts and revenue offices, claiming inheritance. Similarly, powerful interests in hinterlands manipulate tenancy rolls and intimidate smallholders to evict them. Tribal lands – legally protected by the PESA act – are routinely alienated through fraud or force vajiramandravi.com. These land-grab methods fuel deep rural discontent (one root of Maoist insurgencies) and enrich a violent underworld that is often linked to corrupt officials.

In cities the crisis is equally stark. Ambiguous titles enable organized mafias to grab urban fringe property, then demand kickbacks. Authorities estimate that millions of Indians( live in unauthorized settlements or slums, housing built on dubious land claims reuters.com. Unchecked, this unchecked sprawl undermines urban planning. In effect, land disputes and corruption have become a parallel law in many regions. Global organized-crime indices note the presence of a “land mafia” even illegally seizing forest land ocindex.net. At the same time corruption is rampant: studies report pervasive bribery of lower-level officials and collusion with political figures in land deals ocindex.net. In sum, land chaos erodes law and order – it creates vested gangster interests that defy justice and stoke crime.

Strangling Sectors and Spreading Imbalance

The dysfunction in land administration throttles India’s economy by sector. In agriculture, most farmers are too “ownerless” to get bank loans. Ambiguous titles mean land can’t be collateralized. As a result, 41% of small farmers rely on informal moneylenders charging crippling interest prsindia.org (and credit flow to agriculture remains skewed towards large landowners). Credit-starved, these farmers under-invest in productivity and remain trapped in poverty.

Industry and infrastructure face chronic paralysis. Acquiring land for factories, highways or power plants triggers decades of litigation. A striking example is a Noida land case that dragged on for 30 years: only in 2025 did the Supreme Court finally order compensation to farmers after ₹500 cr is still tied up timesofindia.indiatimes.comtimesofindia.indiatimes.com. Such uncertainty scares off private investment in manufacturing and roads, worsening power and logistics shortages.

Cities suffer too. Without accurate land records planners cannot provide services: roads end abruptly, electricity wires go underground, and property tax bases remain opaque. The result is over 65 million people living in informal slums with no secure tenure reuters.com. Central schemes like Smart Cities and AMRUT falter when they lack reliable land data. Moreover, states diverge: those with better land governance (e.g. Gujarat, with advanced surveying) draw more industry, while states like Bihar or Jharkhand lag behind. This fuels regional inequality and migration pressures.

The knock-on to law and order is clear: land disputes already dominate India’s courts prsindia.org, and the paralysed judiciary and bureaucracy (often corrupt in land dealings ocindex.net) buckle under these cases. Without fixing land governance, gains in any sector will be precarious.

Urgency of Reforms

Recognizing the emergency, India is deploying technology and legal reform. The Digital India Land Records Modernization Programme (DILRMP) has already digitized roughly 95% of rural land records since 2016 pib.gov.in. Computerization of titles, e-registries and even linkage to Aadhaar ID are underway pib.gov.in. States are adopting GIS mapping and drone surveys – for instance, Chandigarh now maps parcels with drone imagery and GPS, sharply reducing boundary fraud timesofindia.indiatimes.com. A major innovation is the Unique Land Parcel Identification Number (ULPIN): a 14-digit geo-code assigned to each plot based on its coordinates pib.gov.indolr.gov.in. In time, ULPIN will make every land record unambiguously traceable to its precise location, integrating spatial data with ownership.

Crucially, experts are pushing from presumptive to conclusive titling. Under this model the state would guarantee land titles and compensate in case of errors prsindia.org. Achieving that would require a one-time nationwide survey and legal overhaul of registration laws. The government is moving in that direction: the draft Registration Bill, 2025 envisions a fully online, paperless registry, modernizing the century-old 1908 Act into a tamper-proof digital framework pib.gov.in. This would lock in coherent titles at the time of sale, backed by government insurance.

To speed justice, India is also creating dedicated tribunals. In 2025 the government launched special fast-track courts for property disputes, aiming to settle land cases within 6–12 months legaleye.co.in. These courts employ simplified procedures and linked electronic records. Even the Supreme Court has mandated time-bound processes for compensation (as seen in the Noida judgment timesofindia.indiatimes.com). Meanwhile, linking biometric identity to land is now standard: Aadhaar-based verification is mandatory for property transactions legaleye.co.in, and parliamentary committees have recommended tying Aadhaar/PAN to all deed registrations prsindia.org to eliminate anonymous benami deals.

On the anti-crime front, laws are tightening. The Benami Transactions Act (2016) is being enforced more stringently to crack down on money-laundering through land. Data analytics and even AI could be used to audit suspicious property transfers (tracking huge discrepancies between sale-deed values and cash flows as in recent ED cases timesofindia.indiatimes.com). Police and revenue departments are beginning to share land databases so that local land-grab complaints can be flagged quickly. Civic bodies are also being empowered to spot unplanned colonies early.

Land as a Foundation for Inclusive Growth

Reforming land isn’t just bureaucratic housekeeping – it unlocks broad social and economic gains. With clear titles, smallholders can use land as collateral to secure bank loans prsindia.org, boosting farm productivity and rural incomes. Women benefit too: joint spousal registration and inheritance reforms mean more women gain ownership, improving household welfare. Forest and tribal communities gain firmer claims to ancestral lands under programs like Forest Rights Act, rather than losing them.

Cities become more liveable. Transparent land records enable planned land pooling for urban expansion: states like Punjab’s new pooling policy (BRAP) lets villagers combine and redevelop their land collectively, rather than selling to mafias. Slums and unauthorized colonies can be regularized responsibly (as Delhi’s 2019 law did for 4 million dwellers reuters.com), with secure titles, services and taxation. Accurate land data also widens the municipal tax base, giving local governments funds to improve infrastructure.

Finally, a well-regulated land market helps clamp down on black money. Digital trails for every sale deed (as envisaged by DILRMP and the new Registration Act) would make benami transactions far harder. Currently, real estate is a favoured outlet for undeclared cash; in one raid land speculators were caught moving tens of crores of rupees in unrecorded deals timesofindia.indiatimes.com. Clear, audited land registries would force illicit wealth into legitimate investment or taxation, rather than fueling slush campaigns and graft.

Cutting the Gordian Knot

India’s land crisis is a silent emergency. Its consequences bleed into every sector: perpetuating rural poverty, widening inequality, spawning graft and violence, and stalling projects. The recent 2025 reforms – record digitization, unique parcel IDs, Aadhaar linkage and fast-track courts – offer real hope. But technology alone isn’t enough. Success will demand relentless political will, bureaucratic integrity and citizen engagement.

Without decisive action, development will remain lopsided and hostage to bhumafia empires. Law and order will continue to suffer: remember that 66% of court cases are land cases prsindia.org, and local corruption often centers on land deals ocindex.net. India cannot afford such stagnation. For true growth and social justice – for farmers, entrepreneurs and city-dwellers alike – the nation must finally unravel the knot of bhoomi rights. The time to act is now; the price of delay is the very progress we seek.